A look back at 2014: Editorial

With more pictures being shared around the world than ever before, the need for strong, honest and powerful imagery is blatantly obvious. Christopher Quyen spoke with photographers and photo editors to gain an insight into how the industry changed in 2014.

Amongst cuts to newspaper photo staff and budgets, the most prominent force in this year’s editorial world is the digital surge of content. Long gone are the days where gatekeepers decide what we can and can’t see in terms of news. This year saw everyone, photographers and smartphone-wielding warriors alike, playing a part as witness and reporter around the world. While this may dishearten some professional photographers, the editorial market has grown in some areas due to this digital globalisation. But with the world caught up in critical events and social issues ranging from the MH-17 disaster to protests in Ferguson, Missouri and the Ebola crisis, we are now reaching the eyes and ears of more people imaginable, so the need for powerful, honest photography is more important than ever.

Commission impossible

In this digital world, for many, commissioned work is no longer the editorial photographer’s bread and butter, but there have been some improvements. Mark Murrmann, photo editor of nonprofit news organisation, Mother Jones, found that major publications who prioritise premium reporting and photography are maintaining the landscape for commissioned work. Among these include the Guardian where the head of photography, Roger Tooth, has witnessed a growth in commissions. “We are probably commissioning more than last year, but that reflects the general improvement in the economic climate,” he says. “As long as there is an independent editorial world, we will need good photojournalism.” For Australian New Delhi-based photojournalist, Daniel Berehulak, who is represented through Reportage by Getty Images, this improvement has paved the way for in-depth and concerted reporting. “Working with The New York Times has given me the ability to spend more time on certain issues or assignments. I have been covering the Ebola crisis for over three-and-a-half weeks, while most organisations have only been investing a few days,” says Berehulak.

But for independent news organisations, regular commissions are difficult with limited budgets. Although this affected Mother Jones, it has driven them to deliver exceptional work. “Too many publications are run with an eye on the next quarter’s stock price and not on the long-term reputation and success of the newspaper or magazine. Running news organisations this way has had a distinctly negative impact on the photojournalism industry. That needs to change,” says Murrmann. But with the increased focus on online content, Murrmann has also experienced frustrations of a downward pull on rates paid and the kind of work published. World Press Photo and Pictures of the Year International award winner and photojournalist, Adam Ferguson, has also observed these difficulties. “The media has not worked out how to monetise online readership. Newspaper and magazines used to be a platform that supported a breadth of photojournalists and afforded them the opportunity to document critical events and social issues, but that platform is not as robust as it used to be,” he says. This has led many photographers to crowdfunding, grants and freelance work.

Freelancelot: editorial’s greatest champion

While the old adage claims, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” it doesn’t help when it’s gibberish. Along with the Chicago Sun-Times, Fairfax Media recently cut more than half of their photo staff this year in preference to citizen photojournalism, stock photography and outsourcing. Among these redundancies was photographer Glenn Hunt, who found himself working freelance after the cuts. “The culling of photographers from news departments is short-sighted,” he says. “Since I started freelancing, I realised there’s a lack of communication between journalists and photographers. I was often commissioned by newspapers as a contract photographer. This was limiting as I was only allowed to shoot what I’d been commissioned for, which doesn’t always visually tell the story.” Adam Ferguson has a similar view. “We are losing the articulate, visual narrative created by intelligent photojournalists, but despite the state of the media industry, I don’t think this craft will die,” he says.

But being made redundant from the comfort of a photo department is not necessarily a bad thing. In the fashion world of editorial photography, freelancing seems to be mandatory, as was fashion photographer and Breed Networks founder, Melissa Rodwell’s experience. “The old saying ‘feast or famine’ definitely has rung true for me, from the beginning and to now. Budgets have shrunk and there are now more fashion photographers than ever. And there’s simply not that much work out there,” she says. Although it does require more effort, freelancing can also be quite liberating. “There are definitely fewer editorial assignments available, but in other ways there are more opportunities to tell stories and report on the world through working with NGOs, foundations, nonprofits and producing your own personal projects,” says Ed Kashi from the VII photo agency. Ferguson has also found freedom working on a personal project in Australia. “It’s refreshing to pull away from news and create an original story without any preconceptions. It actually made me realise how working for newspapers and magazines impact the work you create,” he says. While Kashi has experienced the impact of the loss of archive image sales, he remains optimistic. “The loss is hard to make up and requires more time in the field, but it forces one to find alternative sources of income, whether it be lecturing and teaching to book and print sales,” Kashi says. Rodwell’s solution led her to create Breed Networks and to teaching as well.

Shooting at shooters

Neutrality is a luxury no longer afforded to photographers working in areas of conflict. Danger and death have always been a risk in this vocation, but with photojournalists no longer thought of as neutral, the job has become more challenging and dangerous “It’s getting more difficult for Western media organisations to cover conflicts that involve Islamic fundamentalism,” Tooth says. The most tragic example of this was the kidnapping and beheading of photojournalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff, by ISIS. Adam Ferguson who recently survived a helicopter crash in northern Iraq while on assignment experienced the effects of this during his coverage there. “It was frustrating trying to cover the ensuing civil war as I couldn’t go anywhere near ISIS without taking significant risks. In the post 9/11 world, there is a polarisation that renders journalists as targets of kidnapping. For many geopolitical wars we cover, gone are the days when a photojournalist can work unilaterally travelling between opposing forces,” says Ferguson.

Elsewhere, photojournalists are under fire by a different threat: The right to report. “Now we can be targets, on top of having lost our immunity or neutrality. Due to the Internet and raised global awareness of the impact of media and particularly images, photojournalists are more vulnerable than ever,” says Kashi. American documentary photographer, filmmaker, and writer Jon Lowenstein was the winner of the 2014 Dorothea Lange-Paul Taylor Prize for documentary photography. He experienced this during his coverage of the Ferguson [Missouri] unrest where Getty photographer Scott Olsen was arrested for simply doing his job. However, Lowenstein also understands that it was a very complex situation. “For the United States, Ferguson was both a fluid, and at times volatile situation. The protestors were upset. The police were on edge and heavily armed, and there was a component of protestors with guns who also were shooting,” he says. Lowenstein produced a short film of the unrest and also photographed the conflict using an iPhone. “I rarely, if ever, felt restricted from doing my job during the time, but did have to be aware of my personal safety and the safety of my colleagues,” says Lowenstein.

The future in an instant

For Ed Kashi, technology has made it easier to capture images and videos with HDSLR cameras transforming him into a “fully-fledged hybrid, visual storytelling and image maker.” But Melissa Rodwell says technology can be both a blessing and a curse. “It’s a blessing because photographers can easily market themselves through social media, but it’s a curse because your following isn’t always an accurate representation of your talent,” she says. As far as mobile applications go, Instagram has made the biggest impact this year with photographers using the platform as a portfolio to build their audience. For Jon Lowenstein, this rings true with 2014 seeing him use iPhone photography to cover Chicago’s South Side gathering an Instagram following of over 92,000 followers. “People on Instagram are truly beginning to engage. The engagement is the most exciting part as people from all parts of the globe are engaging in dialogue about issues that affect us all,” says Lowenstein. “I think the photographic industry is at its most exciting ever. It’s harder to make a living, but the ability for people to use the photographic language to tell stories and communicate with one another is unprecedented.”

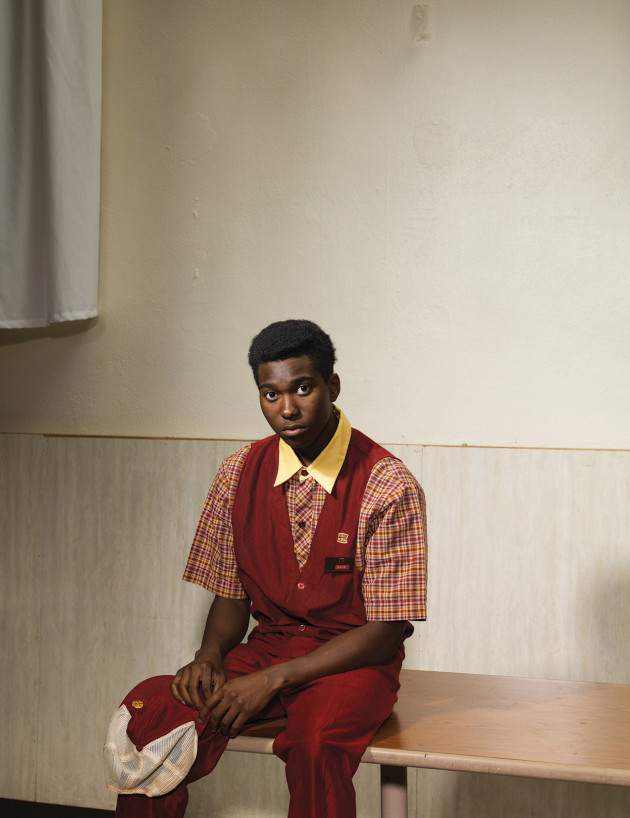

But even with the convenience of technology, some editorial photographers like Rodwell still yearn for the days of film photography. “I come from a film background. I learned how to expose, develop and print both black and white and colour film. My prediction for the future is that photography will return to its original art form by returning to film. At least, that’s what I’m hoping for,” says Rodwell. Lowenstein also continued his use of analog photography this year creating a wet plate collodion studio. He even uses iPhone applications to emulate a nostalgic, analog mood in his Instagram images. It’s almost as if we have entered an age of a digital/analog crossover. Mark Murrmann has observed this desire for photographic artistry resulting in fine art-minded photographers being sent to shoot a reportage assignment like Anastasia Taylor-Lind’s gorgeous series of portraits of protestors. “However, some of this work as gorgeous as it may be, is quite hard to place in a magazine where space is tight,” he says.

20/20 vision

With so much digital imagery readily available online, the need for clarity is extremely important. We are entering an age where the editorial photographer can build their careers with little more than a computer, an Internet connection and a camera. While Adam Ferguson feels like the proliferation of digital imagery is devaluing the traditional role of the photojournalist, he doesn’t resent this. “It’s actually great because it means information is moving and there is a greater climate of transparency. Digital imagery is a democratisation of information, and this is important,” he says. However, whether we choose to build our careers online or in print, it seems like the editorial world will always require strong and honest photography.

Contacts

Daniel Berehulak www.danielberehulak.com

Adam Ferguson www.adamfergusonphoto.com

Glenn Hunt www.glennhunt.com.au

Ed Kashi www.edkashi.com

Jon Lowenstein jonlowenstein.com

Mark Murrmann www.motherjones.com/authors/mark-murrmann

Melissa Rodwell www.melissarodwell.com

Roger Tooth www.theguardian.com/profile/rogertooth