Another disgraceful scandal rocks the photography world

Another scandal has rocked the photography world. And yet again, it involves a photojournalist covering some of the most sensitive topics our society faces. Interestingly, this scandal was initially sparked by an image used by LensCulture to promote a Magnum photo competition. An article written by Benjamin Chesterton, appearing on the website Duck Rabbit, LensCulture and the commodification of rape, questioned the ethics of the use of the image, and the image itself.

Initially reported by PetaPixel, award-winning photographer Souvid Datta has admitted he doctored images, stealing the work of legendary photographer Mary Ellen Mark. Why his decided to steal images in the first place is outrageous to any photographer, but why he decided to take the work of a photographer as recognisable as Mary Ellen Mark is truly bewildering.

The use of Photoshop is inextricably intertwined with our industry and professional practice, but when it comes to photojournalism and documentary, overwhelmingly considered sacrosanct, its use is entirely unacceptable, if not morally and ethically repugnant.

The “doctoring” of images and appropriation of the work of others without clear and obvious attribution is something that the photography community will simply not tolerate. And sadly, a number of other very well regarded photographers have come under the spotlight recently for their use of Photoshop, including Steve McCurry.

But many a photographer's career have been extinguished or at least significantly hampered over transgressions which, at face value, appear to not be as grave as what Datta did. Some noteworthy examples include The Los Angeles Times photographer sacked in 2003 for an altered image, the Associated Press photographer sacked and banned from working for the organisation for removing his shadow from a photo, the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer found to have editted another journalist's camera out of a shot of a Syrian rebel taking cover, or the Getty photographer who altered a golf shot.

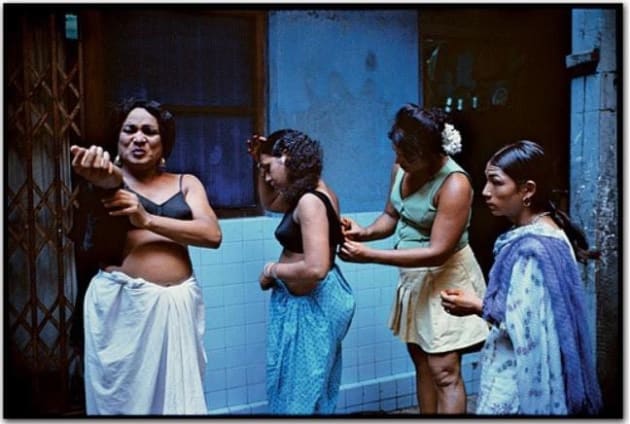

Clearly, this sort of malarkey has been going on for a very long time with differing degrees of severity. But surely by now photographers would learn that it’s simply not acceptable. The accusations relating to Datta are focussed on an image taken in 2014 depicting three women, one of which it has been revealed was copied-and-pasted from a 1978 image by Mark. In a recently interview with TIME magazine, Datta admitted that he did indeed doctor the photo, as well as “appropriating” other photographers’ work as his own.

Born in 1990, during his brief career, Datta has received numerous prestigious awards and grants in the photo industry, from organisations including PDN, the Pulitzer Center, Getty, and Magnum. Some of these include a Getty Images Editorial Grant, an Alexia Foundation award, the Visura Photojournalism Grant as well as a LensCulture/Magnum Photos award, and all this in a career that started just three years ago.

Datta says the photo in question came about while he was documenting sex industry violence in Kolkata, India. After following a girl into a brothel, Datta was dismayed that the girl’s “mentor”, Asma, asked not to be photographed. The photographer says he came across Mary Ellen Mark’s photo, and decided to Photoshop Mark’s subject into his photo to see what it would have looked like had Asma agreed to be photographed.

“The damning mistake came in uploading that image onto my blog,” Datta told TIME. “I did this without accreditation or acknowledgment that it had been tampered with and that it included elements of [Mark’s] image. I wrote the caption as if Asma herself was in this image, not a woman from someone else’s work. In effect, I lied.”

Datta says his original intent wasn’t to profit from the photo but instead to develop his post-processing skills. But the lure of “validation and exposure” eventually led him to publish the photo in an essay with an untruthful caption.

Unfortunately for Datta, it’s not the first time that he’s done something most would call into questions. During his interview with TIME, where he referred to a “dishonest phase of his career,” he admitted to stitching, cloning, and combining others photos. He was also responsible for sharing the work of other photographers work and claiming it as his own, including colleagues Daniele Volpe, Hazel Thompson, and Raul Irani. He also lied in order to conceal those actions before entering them in photo competitions. But for his latest work “as a serious photojournalist,” Datta says he gave his “utmost to uphold principles of respect, journalistic insight, compassion, perspective and perseverance.”

In 2015, Datta shared two of photographer Daniele Volpe’s photos as his own on Facebook. He has since closed his Facebook, Instagram and website as the story broke.

“I cannot begin to say how much I regret having acted in this abhorrent, short-sighted and irresponsible manner,” Datta told TIME. “From here on, I do not know what will happen to me or the stories I have followed. I fear above all that they may remain untold.”

“My credibility has been fundamentally challenged, and I understand the serious implications of that in an industry where

We decided to ask our Facebook following what they thought of Datta's actions, despite his admission of guilt, but the overall responses was of condemnation for a photographer who really should have known better, and possibly would not have come forward unless pushed into a corner.

There a great article in TIME, if you want to read more about this.