The term “alternative processes” covers a multitude of different historical and experimental photographic techniques and mediums developed since the early 1800s. However, one could just as correctly label them traditional processes, but in light of everything digital, and certainly for the newer generation, they certainly seem quite foreign and rather alternative.

Widely considered the first commercially successful form of photography, the daguerreotype was introduced by Frenchman Louis Daguerre around 1839. A mirror-like ‘silvered copper’ plate is exposed in-camera, with a detailed positive image then developed into the metal’s surface. The process sparked a thriving industry for several decades and brought photographic images into the hands of the masses. Fast-forward to the 21st century, and daguerreotypes have long since been superseded and, for the most part, allowed to fade into history.

A contemporary daguerreotypist

One beauty of this process is its longevity and many daguerreotypes still exist in collections all around the world. American photographer Jerry Spagnoli recalls his awe upon discovering the medium back in 1994. “I saw one and I was immediately stuck by the quality of the image.” Spagnoli was hooked and has spent the last two decades studying and mastering this complicated process. Today, he is regarded as the world’s most prominent living Daguerreotypist, having undertaken prominent commissions, published several books and his work held in many major collections around the world.

Spagnoli’s personal work is primarily divided into two categories: portraiture and his long-term street documentary series The Last Great Daguerreian Survey of the 20th Century. The choice to lug a metal-plate-loaded large-format camera around the streets of Manhattan, capturing such events as the September 11 bombings and President Obama’s inauguration, may seem somewhat odd to some. But for Spagnoli, a major strength of using daguerreotypes to shoot this work lies in its ability to convey, what he describes as an “immediacy and direct engagement with the subject.” For anyone who’s viewed one, it’s undeniable that daguerreotypes are indeed best experienced in person. “It’s easy to feel yourself in that space because of the way the daguerreotype interacts with the light and transmits the light back to the viewer. So I thought it was the ideal medium to do a documentary project for people in the future to look at, so that in some way they would feel themselves present in the moment with me.”

Wet plate pursuits

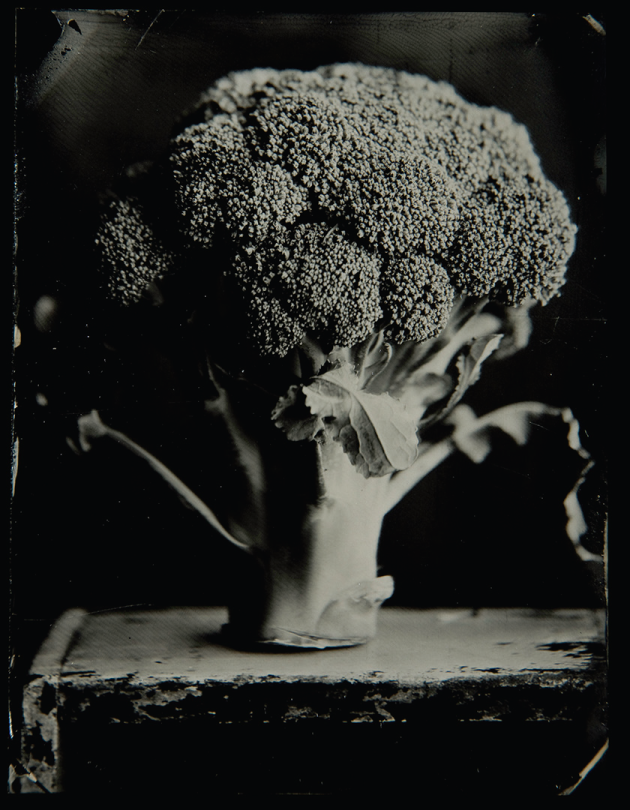

Chuck Bradley is a Pennsylvanian export, who has called Australia home for the past 28 years. He embarked on his own alternative process adventure several years ago. Only a couple decades after its birth, daguerreotypes were all but replaced by the wet plate collodion process, where one side of a clean glass plate is coated with a thin layer of collodion. This somewhat inconvenient medium required the photographic material to be coated, sensitised, exposed and developed, all within a timeframe of only fifteen minutes. A portable darkroom was needed for any fieldwork, and the result is a glass plate positive image, commonly known as an ambrotype. That this difficult process was superseded within about 30 years should really come as no great surprise.

For Bradley, beginning this challenging undertaking was in fact a way of reconnecting to his photographic origins. He had worked as a photographer long before the digital era and relished getting back to using his hands to craft, as he puts it. At that time, there were few who were doing the wet plate process in Australia, and simply sourcing the chemistry took about 12 months. Bradley eventually obtained the necessary materials and was able to experiment with, and subsequently master, the wet plate process. He produced a series of notable portraits and still life works, which though not his focus today, sit comfortably beside his recent historical and maritime-themed projects.

Creating a legacy

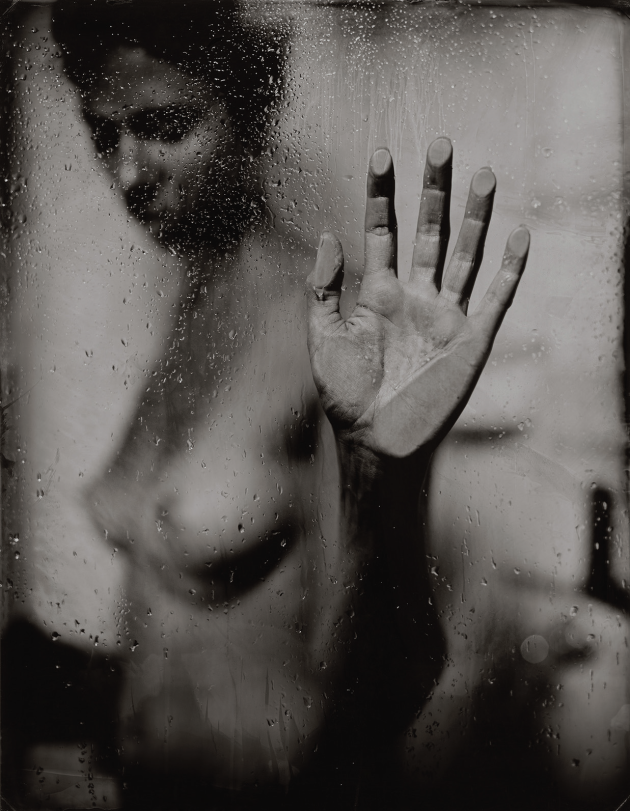

Working with both the wet plate collodion and daguerreotype mediums, is Craig Tuffin who is based in Kingscliff in northern NSW. He admits it sounds somewhat melodramatic, but a near-death experience was what sparked him to focus his photographic practice towards alternative processes. After suffering a near-fatal head injury in 2005 and being confronted with the very real fact of his own mortality, Tuffin was forced to reconsider his ‘legacy’ as an artist. “My work up to that date didn’t really have anything that it contributed towards,” he admits. Resolved to change this, Tuffin has devoted the last seven years to alternative processes and large-format photography.

Tuffin is predominantly a portrait photographer, and much of his work, such as his series As Faulty As We Are, is underpinned with a deeper sociological intent. “You get to create a relationship with the people involved. It’s very much a collaboration.” The complex nature of the process, the need for a darkroom on location and extremely tight timeframes in which to work would deter most from this process, but Tuffin sees it as a challenge. He has converted his caravan into a darkroom, and a recent experiment saw Tuffin attempt to transform his big work van into a camera. “We built everything from scratch, just hoping that it was going to work”. It did work, and Tuffin can now drive around in one of Australia’s largest large-format cameras.

Palladium conservation

No stranger himself to working in challenging conditions, Liam Lynch has combined his love of the natural world with the remarkable process of palladium printing. Lynch discovered this monochromatic platinum printing process in 2009 at a Nick Brandt exhibition. “I was immediately captivated by the depth and tonal range that I’d not seen before.” Lynch is a strong advocate for safety and respects the dangers involved. “Capturing images in the wild has its inherent risks. Add to this that I also spend a lot of time underwater where the risks are even more apparent, and I try to be as prepared as I can be with careful planning and relying on local knowledge whenever possible.”

Like many traditional processes, palladium works need to be seen in person to be fully appreciated. Each print is a handmade one-off and exhibits an impressive tonal range, which is able to do justice to the incredible natural beauty that Lynch’s images capture. From swimming with whales in Tonga to traipsing through the jungles of Borneo, Lynch transports the viewer to places of resounding wonder and incredible beauty.

Botanical experiments

The term alternative process covers a rather broad range of mediums, and there is certainly room for experimentation across the board. Polish-born Renata Buziak certainly fits into the experimental category, and although her ‘biochrome’ process has its roots in traditional processes of the past, she is definitely breaking new ground for the medium. Buziak’s “fertilisation of photographic materials, using vegetation, directly focuses on the significance of time and change through decomposition”. This decomposition takes place upon photographic materials, resulting in impressive, colourful compositions.

Buziak experiments on various materials, yet analogue photographic materials are crucial to her practice. “I use outdated, unwanted materials as much as possible, which allows for a wider range of resources and recycling”. She always works collaboratively. And she says her “biochromes themselves are collaborations with natural processes”. Not unlike her work, Buziak’s practice is ever-changing and growing, and she relishes the opportunity to work with others. “Sharing and complementing each other’s skills and ideas, coming up with projects and solutions together allows for exciting dialogues, exchanges and new work that would never exist otherwise. I think that collaborations not only enrich our practice, but also our lives”.

For love or money

It’s no secret that forging a successful career in photography is no mean feat. Spagnoli considers himself fortunate to be “the only one doing what I do, in the way that I do it.” Based in the global art and photography epicentre of New York, Spagnoli has been able to build a successful career around daguerreotypes. Through what he considers ‘a confluence of events’, he has been able to combine commissions with the sales of his own work to form a successful business. Despite this, he is adamant that financial gain has never been his motivator. “What you focus on is engaging that tradition and perhaps informing it with your own ideas. That’s my main focus with all of my work; to engage with the medium in a way that perhaps moves a particular discussion forward.”

In Australia, photographers are swimming in a much smaller pond than New York, but for those motivated enough to persist, there is always hope. For Bradley, there was never any real aim of financial return from his alternative process work. The satisfaction of delving into and mastering the craft was always the true stimulus. Likewise, the motivation for Tuffin to commit to alternative processes did not lie in seeking financial gain. Ultimately however, every photographer needs to earn a living. Fortunately, after taking the gamble of putting his commercial work totally aside, and after years of dedication and hard work, Tuffin is starting to experience to fruits of his labour. He strongly believes that “like any artist you’ve got to be prepared to step out and take the chance.” Major galleries are now starting to represent his work, and paid commissions continue to roll in.

In Lynch’s case, it is an unwavering passion for the natural world and conservation that pushes him to keep creating his palladium work. “I’d like to think that in some small way my images could possibly inspire the viewer to consider conservation of the species”. As for it being commercially viable? “Not at this stage, but it’s early days and my commercial work supports the artistic pursuits, so I’m fortunate in that way.” For Buziak, lifelong fascination and love of plants is what fuels her experimental work. Passion alone is fortunately not her only backing. Buziak has growing national and international recognition, and currently has support through her ongoing doctoral studies with the Queensland College of Art in Brisbane.

The future of the past

While uncertain by any means, the general consensus seems to be that alternative processes are indeed alive and will be for some time to come. Lynch is optimistic. “I’d like to think the palladium process will be around as long as the life expectancy of the prints themselves [1,000 years, or more]”. Spagnoli hopes to add to the lineage of his medium, and plans to put together a manual, which would be released posthumously. “Since I’ve kind of moved the process into usability, within the context of the 21st century, I do feel I have an obligation to document what it is I do and what it is I’ve learned.” He also teaches workshops, as does Tuffin, who is passionate about educating and is partnered with RMIT in Melbourne.

A lot has changed since Bradley’s first forays into sourcing materials took a whole year. A tireless campaigner for all things hands-on, Ellie Young, who runs Gold Street Studios in Melbourne, has cultivated a school dedicated to the continuation and growth of alternative processes. Gold Street is a veritable hub for facilitating a multitude of workshops, hosting exhibitions, sourcing and selling materials and sharing knowledge. “Skilled tutors are bought in from around Australia and internationally. They have a passion and vast knowledge of their process with an ability to impart information”. Young urges anyone to give it a go. “Some processes require no equipment except a brush, paper and water.” Far from dead, alternative process is indeed alive and thriving in Australia and beyond, with talented practitioners dedicated to ensuring these historically based art forms live on and grow. With the over saturation of digital and instantaneous imagery in our lives, it might very well be hands-on and alternative processes that many turn back to in their search for something tangible.

Contacts

Chuck Bradley: www.chuckbradley.com.au

Renata Buziak: www.renata-buziak.com

Gold Street Studios: www.goldstreetstudios.com.au

Liam Lynch: www.liamlynchphotography.com.au

Jerry Spagnoli: www.jerryspagnoli.com

Craig Tuffin: www.craigtuffin.com