How to get the most out of the existing markets for documentary photography

I work as a producer with visual storytellers and artists emerging from the documentary tradition. With my current projects I’m involved in all stages of producing and distributing the work of the photographer and have explored markets, old and new, where this work can live and thrive.

In March, I’ll be in Melbourne teaching a Lab at RMIT University where we’ll talk about taking advantages of markets outside of the editorial media and building your value as a storyteller based on self-assigned work.

Below are some tips on how to significantly improve your self-worth and the health of your projects (and get a fair treatment for your work) within traditional go-to markets and platforms for photography.

We all know making documentary work takes dedication. We don’t go into it to get rich. To quote my colleague Adrian Evans, a picture editor and founder of Panos Pictures, “As long as you make peace with the fact that our business is not super profitable, you’re gonna be just fine”.

But we still need to pay our bills, support our adventure spirit and the crazy travel schedule.

I know so many photographers like you with a good story to tell. You’ve invested a significant amount of time and portion of your soul and researched it well. Given that you have a good eye, chances are your project is visually beautiful and contributes to understanding the issue in question.

But if you’re relying on just one or two of the traditional photography platforms and distribution channels, the likelihood of you being able to support your documentary work and present it in the way that will do it justice, are small, and getting smaller.

The photography market is not dead. Photojournalism in particular is more alive than ever, but our value chain is broken. We are dealing with one of the slowest creative markets to change out there. The industry is very small and resistant to merging, collaborating and borrowing from other markets.

Sure, we can sit around and complain about it (for those of you in need of burning some fumes, I highly recommend watching the satirical animated series Fuck Yeah Photographer. And the promise of exposure and other nonsense can begin to drive you mad.

Or we can take a moment to look how our own actions contribute to undermining our hard work and how to adjust our behaviour to be able to continue doing what we are doing and reach new audiences.

Editorial media

There’s not much point in bad-mouthing newspapers and magazines for their en masse inability to support serious visual journalism, both financially and contextually. The decline of the editorial media as a market for photojournalism has been going on for decades and it’s not the fault of the editors who are offering you miserable fees for your work. There is value in exposing your work to millions that read national papers, but someone has to pay for its production adequately.

- Limit the usage of your material online in time so that you can license it to someone else.

- Don’t give [large] publications free content unless someone else paid for your work and you have an obligation to disseminate it via media outlet.

- Don’t give away video work for $500 that cost you thousands of dollars to produce.

- Most importantly, don’t work with editors and publications who don’t see you as human beings.

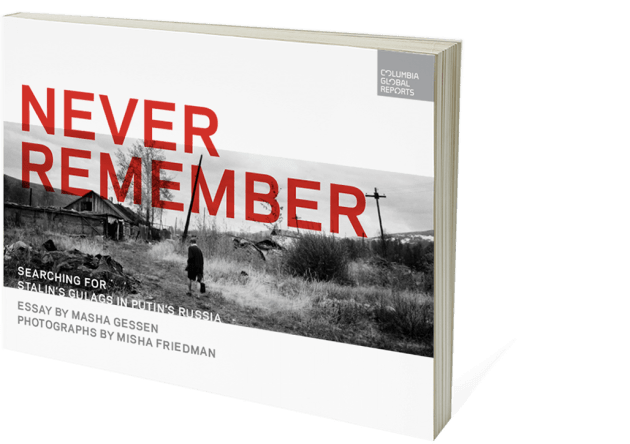

Book publishing

I personally love photo books and have boxes of them in storage in my hometown of Moscow and in New York. Photo books are important as they give you the ultimate control over your content and its presentation, however, in recent years I worry increasingly about how they fit into the bigger picture. How many people actually see them and how do they benefit the author?

Unlike artist books published by big art publishers, photography books usually have a limited run and cost money, not many people make any royalties. If you can’t find the publisher who is willing to invest into your book, at least a tiny bit, it probably means that your book hasn’t generated any interest within the limited circle of photo book publishers.

- Don’t go with the publisher who asks you to cover all printing costs and do the promotion of the book yourself. These are printers, not publishers.

- Think outside the box and come up with an idea for a book that might interest other publishers, outside of the phonebook pool. They will give you access to a much larger audience but also bring in some real money.

‘Kosmos’ a children’s book collaboration between photojournalist Dmitry Kostyukov and artist Zina Surova about the exploration of space (2012).

NGOs and commissioned work

Working on commission to communicate someone else’s message is a complicated beast, but it can help fund work on your subject matter of choice or long-term projects.

Non-governmental organisations have traditionally been a big market for visual journalism. Our goals are aligned for the most part – to inform society and cause significant change – but the methods are very different. You can detect an NGO-commissioned video from afar without reading the credits.

Photographers used to produce work for NGOs for free in return for access because they were on assignment from big magazines who were paying them good fees and expenses. Now, the assignments have almost vanished and the fees diminished, but many NGOs still expect you to work for free for access.

Remember, NGOs have messages to communicate to both their funders and target audiences. They have communication campaign budgets specifically dedicated to producing these materials.

- When shooting for an NGO, charge a day rate and expenses just like you would from any other client.

- When you hear “We are extremely invested in supporting young talent”, “We are still growing our user base” or “We are an exciting brand to be associated with” - well, if you’ve read this far, you already know the answer to that.

International Committee of the Red Cross.

Video

You have most likely produced videos for clients entirely by yourself and received no or almost no compensation for it. Your editorial clients expect you to submit video and sound on top of stills if you are on assignment for them or want to get published at all. Most of the time they offer you no extra fee or expenses to cover for video production and editing.

If you are producing moving image on a consistent basis and want to get better at this, consider looking at video in the context of film and broadcasting which is a healthy and well-functioning industry.

In my experience, films produced by photographers have a different visual quality and sensibility than shorts produced by filmmakers who approach them as gammas/exercise towards a feature documentary. Good films by photographers are condensed and well researched and are visually stunning.

‘When The Spirit Moves’ by Jared Moossy and Justin MaxonThanks to video-on-demand and digital broadcasting, short films now have a long life beyond festival screenings. Shorts can get commissioned by and licensed to traditional TV, digital broadcasters (CNN’s Great Big Story) and selective old media outlets who take video production seriously (The Guardian Films and NYT Op-Docs). They will pay you thousands of dollars. Festivals pay screening fees (more likely for features and mid-length films, than shorts). And with a relevant distributor your films can end up on a digital on-demand platform or in educational distribution for university libraries.

'Kill List’ by Ed Ou and Aurora Almendral for NBC Left Field- Don’t put your films on Vimeo with no password protection. At least not until you exhaust all opportunities to get them broadcasted or streamed for a fee.

- Research your local market to find documentary and short film festivals, film programmers working with exhibition venues and cinemas, broadcasting TV commissioners, and maybe even a film distributor specialising in shorts.

Exhibitions

Exhibitions are an incredible way of wrapping up thoughtful long-term projects and presenting them to the audience. Like any platform you need to understand why you’re doing it. Is it a festival exhibition to promote your book or film, a gallery show to sell prints, or a museum show that presents a serious inquiry into the theme of the curator’s choice, and also raises your value in the context of the art world?

While gallery shows usually have a pretty straightforward commercial arrangement with the artist based on percentage from sales, festivals and museums policies vary in their level of appreciation of the work that photographers put into making content.

I’ve encountered scenarios where a massive museum exhibition presented by a respected curator tours several locations, gets tens of thousands of visitors and doesn’t pay fees to photographers. Think about it, everyone is getting paid - the curator, the museum staff, the publisher who is selling the catalog, the museum itself via ticket revenue – the only one who is not paid is the content provider. There are too many out there that expect you to pay production costs and don’t offer any funds for expenses or copyright fees.

Festivals, and especially photography festivals, are also guilty of that. Festivals get funding from local governments, art councils, and brands. They should be able to afford to pay.

- Don’t buy into any of the “We are a non-profit”, “We are all volunteers here” and “You’re gonna get exposure” stuff. Someone is getting paid to run the show.

- Put a price tag on showing your work. Always ask for compensation, at least for expenses.

It’s an exciting time to be a photographer. But we have to be willing to experiment, stand up for ourselves and our work, and work collaboratively with others. This is my favourite part. I can’t stress enough how important it is to collaborate with others from different fields and strands of storytelling to make excellent work.

Don’t try to do everything yourself. Approach people outside of your skill set – cinematographers, writers, sound designers, choreographers, writers - hang out with them and learn how they operate in their respective markets. Also, be generous when telling them about photography.

I believe that once we become more open and inclusive of other storytellers, our industry will heal faster.