The Year in Review - Editorial in 2015

The age of independence is here. Editorial photographers have evolved beyond the bread and butter of commissioned work and are now adjusting their focus towards what is personal to them. While media giants still dominate the field, visual storytellers are going against the grain to get their voice, vision and story heard. Christopher Quyen talks with these photographers to see just what 2015 delivered.

To try to look into the world of editorial photography this year is like stargazing, except you have to filter through light pollution, skyscrapers and seagulls to catch a glimpse of something that shines. Every day, billions of images are being shared across the world amongst media giants and magazines, online publications and personal blogs. But when something does shine, the impact is massive, such as the image of drowned toddler, Aylan Kurdi, affecting the hearts of people and sparking a worldwide call-to-action for Syrian refugees.

The online impact has changed the market for commissioned work and assignments in both positive and negative ways. It has also encouraged editorial photographers to find their own voice and identity in the clutter using social media. However, while we do indeed live in a digital world, the model of staying relevant in the editorial industry as a photographer using traditional media outlets is still very much intact and integral to the working editorial photographer. It is now a balance between staying relevant, offline and online, and having a story to tell.

Self-assigned shooters

The age of independence has reached editorial photographers. While commissioned work and assignments are still very important to the industry, shooters are now chasing their own stories and using different media platforms to share their work. Sim Chi Yin is amongst this breed of photographers dedicated to shedding some light on stories that are personal to them. Based in Beijing, she’s a member of VII Photo Agency, and in 2013 was a finalist for the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography with a personal project on Chinese gold miners.

One of Sim’s stories is a four-year project, Dying to Breathe, which explores China’s leading occupation-related disease, silicosis. In her exploration, she chose to focus very closely on one subject, Mr. He, who was in the final stages of silicosis. “The reason why I chose to focus on Mr. He was to show people what the final stages of silicosis looked like. Not many people know what silicosis is like in the long term,” she says, “and the only way to move people is to be very close and intimate with someone.” However, chasing stories that aren’t commissioned by magazines often means a lot of time is spent on business to cover financial costs and working with editors to get the story out. “The story has been very difficult to get out, and up until now, it hasn’t been printed,” she says. But Sim believes that most photojournalists didn’t choose the profession for money, and that stories such as Mr. He’s are valuable and worth the effort.

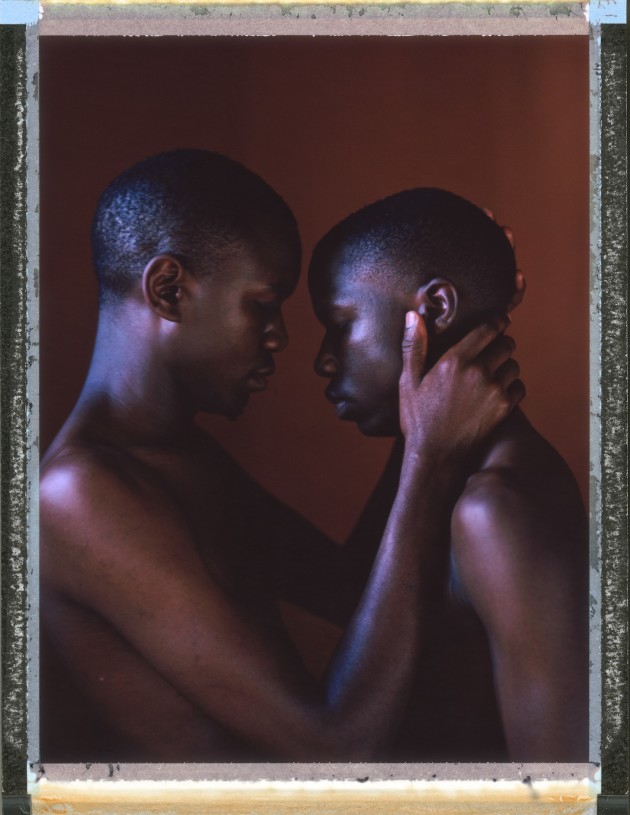

Robin Hammond has also dedicated his photography career to exploring a story that is important to him. The body of work, Where Love is Illegal, is as a Witness Change project that explores homosexuality and homophobia in Africa. Witness Change is a non-profit organisation launched by Hammond that “produces highly visual storytelling on seldom-addressed human rights abuses”, with the aim of transforming opinions, opening minds, and changing policies.

Before he commenced with his independent work, Hammond felt unfulfilled from his commissioned work. “I had this idea that magazines would support in-depth and long-term projects, but because of budgets, you only can shoot for a few days and you just end up confirming stereotypes and don’t have time to discover something new,” he says. That was when he decided that personal work was the only way he wanted to operate as a photographer. “The best work out there is a photographer’s personal work because they have the time to immerse themselves and discover new perspectives on things.”

Financing the project has been difficult as it was self-initiated. Small things, like a grant from Getty Images, help from friends, and piggy-backing the project on top of other assignments are a few things Hammond has done to keep the project alive. To support his project, he has used traditional media outlets and created an online community of over 100,000 followers using social media where he encourages others to share their own stories of discrimination and what they’re going through. Donations are also encouraged that go towards supporting three grassroots LGBTQI organisations operating in Africa.

Social media and technology

It is undeniable that technology and social media are affecting the editorial industry, and are connecting photographers to a larger audience. Recovering from a broken arm this year, M. Scott Brauer, who runs the blog about photojournalism, dvafoto.com, with Matt Lutton, has seen the internet contribute to his pool of clients. “Editors see my work in other publications or shared on social media, and they get in touch,” he says. “I wouldn't be a photographer if not for the internet. I'm from Montana, lived in China for a few years, and now based in Boston. None of those places are hotbeds of editorial photography and only in Boston am I close enough for it to be affordable to meet with editors in New York or DC. But I can get my work to editors so easily now.”

Photojournalist and Robert Capa Gold Medalist, Ashley Gilbertson, has also seen the effects of the internet on the editorial front with media outlets pursuing online-only publications. “My projects for clients like The Queens Diamond Jubilee Trust and UNICEF are often for outlets different to print, such as online only, social media campaigns, exhibition, and so on. It’s an interesting and often new space to work within,” he says. Like Brauer, he sees social media platforms, such as Instagram, as an integral tool to utilise as a photographer. “It’s definitely a part of how clients select you now. It’s also a direct way to engage with readers and even introduce subjects to tell their own stories.”

As for photography technology, the use of mirrorless cameras has been replacing photojournalist’s DSLRs. “I’ve actually traded in my DSLR for a Sony A7S, which I use with my Canon lenses,” says Sim. “Because I use an adaptor, I have to manual focus, but it’s great to be able to use a lighter camera for professional work.” The opportunity to work with film on editorial assignments has also decreased. “I’ve found less and less of a space in which I can shoot on film. In the past, I’ve always relied a lot on my Rolleiflex 2.8F, but in the last 12 months, I’ve only had one opportunity to use it on a job,” says Gilbertson.

Traditions die hard

While the editorial industry has become more fluid, it hasn’t replaced traditional pathways in the industry. Photographer and Creative Director of Art + Design Magazine, David Leslie Anthony, found that the editorial world of fashion has resisted the social media beast. “One of my editors recently told me that he doesn’t look for new photographers on social media,” says Anthony. He stresses that because social media can’t teach you the skills to become a working photographer, it is harder for clients to trust their project’s budget to newer photographers. In today’s market, professionals need to be able to prove their ability in both photography and business, and build up their name and reputation over time. “Young photographers need to spend more time assisting,” he says. “There is so much you can learn when assisting, and one of the most important aspects is business.”

Open my world

Despite shrinking budgets, the fluidity of the market has provided more room for exploration. Photojournalist, Natalie Keyssar, whose coverage of the police’s perspective in Ferguson, Missouri, got the front cover of TIME magazine. She believes that the editorial world is becoming more free and creative. “I think the proliferation of digital photography and social media seems to be driving people to really find themselves and their own visual language, and it’s opening the door to more free, creative ways to tell stories with photographs,” she says. While there is not a great deal of money in photojournalism, the market has placed more value on stories that are “narrative, authentic and documentary-influenced,” according to Keyssar, which places photojournalists with in-depth projects in a good position. “I’m grateful to say there's a real appetite out there for this stuff.” Sim has also seen the market preferring a more artistic look in photojournalism. “The desire for an aestheticised, even fine-art look has become trendy in photojournalism,” she says.

Digital life

The online world was clearly king in the editorial world over the last year. “There continues to be more of a push for online-first assignments, even from print publications. There are a few online-only publications that I've worked for recently that have been paying great rates,” says Brauer. It is easy to see that this will soon become the future as traditional media outlets, like print, feel the strain of continually shrinking budgets. Our environment has become technology, our lives have moved online and editorial photographers will have to exist both in the online and offline world to stay competitive in the market. And chasing work for online-only publication may well become the new norm.