The thin green line - conservation photography and its impact

Since 2008, an average of 26.4 million people per year have been displaced by natural disasters. As our consumption-based habits further fuel the climactic conditions that spur such events, humanity faces a time where the term “climate change” graces the headlines of our newspapers at an ever-increasing rate and photographers’ portrayal of these events is more often seen through the lens of “conservation”. Sam Edmonds investigates the shift of climate issues from the periphery to front and centre of news media and photojournalism’s new shade of green.

Conservation photography has traditionally been a part of documentary practice that takes place only at the furthest reaches of the globe. While the greats of National Geographic have been heralded for their coverage of stories in the driest deserts of Africa or on the coldest ice sheets of Antarctica, as global climate change and environmental issues continue to increase in both frequency and severity, contemporary photojournalists are finding work covering such issues closer to home. At this stage in economic and industrial development, with the need to more seriously reflect upon our role on the planet, conservation photography is evolving to suit its new role as a more frequent theme in mainstream media. But in the wake of journalism’s embrace of both visual and written climate change nomenclature, the ethical implications of reporting on climate science are coming to light along with a redefinition of the line between journalism and activism. And while the ominous nature of climate change reportage may be a tough pill to swallow, the need for traction amongst a young and highly visually literate audience puts photography at the forefront of communicating the future of our species.

Fanning the flames

May 1st, 2016 saw the start of what may become the costliest natural disaster in Canadian history, when a wildfire ignited near the community of Fort McMurray, Alberta. Over the following six weeks, approximately 2,400 homes were destroyed and an estimated nine billion Canadian dollars of damage was inflicted. But what makes the Fort McMurray fire particularly interesting was the media reporting that ensued as several of the world’s largest publications covered the story as a climate change issue. In what surely fanned the flames of debate surrounding economics versus ecology, the town’s role as the gateway to Canada’s oil sands – one of the most destructive resource extraction sites on the planet – was ironically cited as part of the catalyst for what destroyed it: record-breaking temperatures in the area causing dried boreal forest and early snow melt that led to an increase in wildfires.

Ian Willms is a Canadian documentary photographer and photojournalist that, in addition to covering the Alberta fire for The New York Times, has been visiting Fort McMurray for the past six years for a long-term project examining the town’s changing landscape. Willms’ body of work on the area will seek to explore the crossroads between different cultures, different ideas of the economy, the conflict between economy and ecology, and the issue between sustainably and immediate benefits. This exploration has put him somewhat at odds with the media’s take on Fort McMurray. “I’m certainly hesitant to jump on that bandwagon because really what I’m doing up in Fort McMurray is more of an historical document about the changes that have been occurring there over years,” he says. While some publications were certainly quick to jump on this climate-change bandwagon, Willms posits that at this stage, the diagnosis might just be speculation. “It’s hard to say in any situation what climate change is causing, and what it’s not causing, and it’s a very heated argument, especially in Fort McMurray where people there depend on the oil and gas industry for their livelihood,” he says. “From a humanistic perspective, sure you could make the argument that that fire is a result of climate change, but you could also make the argument that it’s not, and for somebody who’s sitting there who lost their house to that fire, it’s a pretty tough wound to open up.”

Willms maintains that his publisher was asking valid questions about the issue, but the Toronto-based photographer believes that in doing so, we should be careful to understand what arguing for climate-change really means for the future of photojournalism. “It’s a tough thing to make a case for in journalism – to go to a person whose town flooded and say, ‘Well, your town flooded because of climate change, so I’m going to cover it from this angle’ and they say, ‘The town flooded fifty years ago, too’,” says Willms. “What do you do as a storyteller that’s trying to be objective, when you’re covering an issue that the population doesn’t seem to agree on and the science is unfolding as we speak? I don’t doubt in my heart that it’s a big problem, but you’re really pushing the line between journalism and activism when you’re reporting on climate change.”

Preaching to the choir

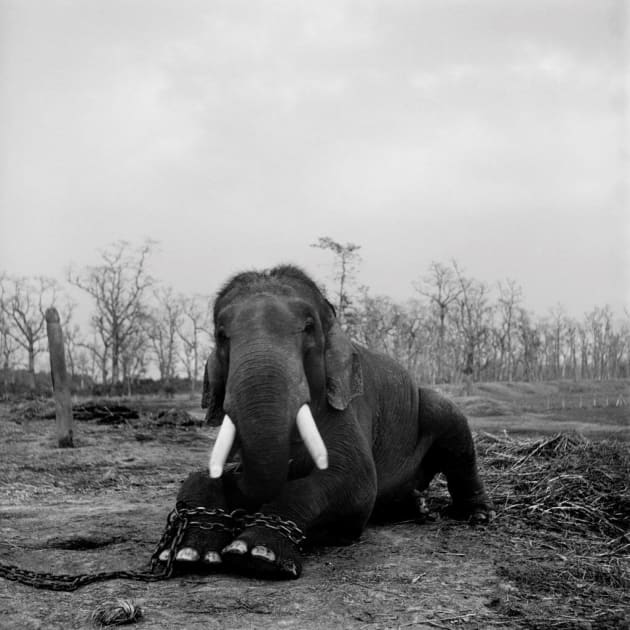

Evidently, a need to maintain journalistic integrity is axiomatic to the communication of any conservation or climate change story, but for Australian documentary photographer Patrick Brown, who is represented by Panos Pictures, the line between journalism and activism can be crossed simply by using the very term “conservation photographer”. Best known for his long-term body of work, Trading to Extinction, which examines the commercialisation of the illegal animal trade, Brown has launched his career in documentary photography by visually addressing one of Asia’s long-standing conservation issues, but says that he consciously avoids labelling himself as anything other than a documentarian. “By labelling yourself as a conservation photographer, you’re labelling yourself an activist, and that is automatically going to alienate you from a large portion of the population. In my view, you are going to change more opinions and more perception if you show people what you have witnessed, not dictate to them.” It’s in this way that Brown points to the importance of recognising the ability of your audience. “You are dealing with an incredibly articulate, visually literate audience that can make up its own mind,” he says. “And as soon as you start to label yourself a conservationist photographer, you’ve already shot yourself in the foot.”

As Brown further elaborates, we are now living at a time where the ability of photographers to recognise and cater to their audience will essentially be make-or-break for the future of our planet. While a long legacy of what was essentially wildlife photography of the sixties and seventies laid the foundation blocks for our perception of wild nature, Brown asserts that a shift has taken place in which that same strand of documentary is now pointing the lens at us – and we are more willing to listen. But as he makes clear, maybe we shouldn’t be turning to The New York Times for dissemination of climate or conservation photography when those who really have the power to make change might be too young to be reading such a publication. “How many young adults are reading The New York Times? It’s more for a mature audience and they have already made their political choices when they were in their early twenties. It’s the younger publications that seem to be more in tune with the environment than the old, mainstream media,” he says. “That’s where you will be able to gain your traction to be able to get people to look at the world in a different way. And they are the future generation that will control the future of the planet, politically and morally.”

But while Brown’s argument for the autonomy of photographers from both the “conservation” label and working with the vested interests of NGOs may seem the most logical when advocating for effective independent storytelling, Melbourne-based photographer and videographer, Tim Watters argues that visual media’s role within the work of large NGOs can spur conservation efforts by other, more direct means. Watters’ extensive history working with non-government organisations, such as Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, became the basis for his understanding of communicating on behalf of such groups, but several instances throughout his career have also proven the role of photographs to directly affect legislation or the understanding of conservation policing bodies.

This was made abundantly clear during Sea Shepherd’s “Operation Driftnet” campaign, on which Watters’ images of illegal fishing practices as presented to Interpol and the UN by the former’s naval captains, resulted in the shut-down of 100 fishing vessels and the suspension of licenses from those involved – an effort that was only made possible by the images’ two-pronged effect on both a general audience and on those in power to make the change. “The images we were able to capture really served two roles – they were able to educate people about what was happening, and gain an emotional connection. But an important other role was that the relevant governing bodies were made aware,” says Watters. “So, the supporters of the world supported via donations which allowed the Sea Shepherd vessels to stay down there and interfere using direct action, but on the other side, getting all those photographic documents to the governing bodies saw the vessels suspended. Without these photos, all these governing bodies would have known as little as the individuals that support us.”

It’s in this way that Watters points to the megaphone effect of NGOs when communicating issues to an audience, and while this may only communicate the journalistic message to an already converted following of the organisation, it’s the power of establishment, strength in numbers, and availability of resources that organisations have at their disposal that serve to amplify their photographic voice. As Watters admits, while his photographs for “Operation Driftnet” were incredibly successful, he doubts the ability of pictures he would have shot independently in causing the same stir. “If I would have bought a tinny, gone out and started documenting this issue, I doubt that it would have had the same effect,” he says.

Natural aesthetics

Seemingly in harmony with Brown’s sentiment of independence from the term conservation photographer in documentary and news contexts, editorial outlets for natural history and biology have long accepted the conservation message inherent in their visual communication without a need to underline it. But in the world of National Geographic, The Smithsonian, and equally for Chrissie Goldrick, editor-in-chief and previous picture editor of 14 years at Australian Geographic, the beauty of the natural world is paramount when eliciting an emotional response from the viewer. As Goldrick explains, the need for preservation is simply a given in most Australian Geographic stories. “Our magazine is a geographical magazine, so basically it’s about the Earth, it’s about the land and the way we treat that land,” she says. “Clearly, in a magazine in which that is the main editorial focus, there is a conservation element to it because most of the time when we are reporting on natural history, we are addressing the threat to that natural history and climate change, increased loss of habitat, etc.”

But while the conservation message is a constant, Goldrick says the sobering nature of such communiqués are often made more palatable by aesthetics. “People can become very switched off when reading these stories of climate change and loss, so we use photography to really engage people, to get their attention and what we hope is that they understand the issue,” she says. “The way we do that is not really by showing the problem. What we try and do is show the beauty of nature and show people what we all have to lose, rather than what we’ve lost already.”

In addition to recognising the sensitivities of an audience when consuming visual media that so often speaks of impending environmental destruction or the end of an innocent species, Goldrick feels that the job of disseminating information about conservation issues is made more complex simply by the plethora of images to which we are exposed every day. “Learning about the natural world, whether through the biology or the Aboriginal/cultural people in Australia, it is not the most easily consumed information when you’ve got so many other things vying for attention,” she says.

However, the result of this is arguably a doubled-edged effect: while the voice of those expressing concern for our ecological future is often drowned out by the sheer amount of other photographs to which we are exposed, this mass of imagery has actually made us better at understanding what a good photograph is (at least, in an aesthetic sense). The proof of this, says Goldrick, can be found on social media every day. “We have this idea that we are so bombarded by photographs and therefore the standard of what counts as good has dropped over the years… but what I see on Instagram is the opposite of that, and really amazing photographs getting a really big reaction,” she says. For the team at Australian Geographic, this serves to corroborate their mantra that the way to educate and inspire about acting on conservation issues is through spectacular imagery. “We spend serious budget every year in the magazine to produce beautiful and original material that is good quality because we need to reinforce the fact that this is an important part of people’s lives – it is important to consider the environment around them because once it’s gone, it’s gone forever,” says Goldrick.

Shifting perspective

While an aesthetic appreciation of the world around us is arguably one of the most effective tools for encouraging a need for conservation, some would argue that the history of this tactic has been somewhat predicated upon only seeing the natural world through professional photographers’ eyes and perpetuating our only conception of ecological issues through the lens of Western people who are almost solely those socioeconomically privileged enough to call photography their career or their full-time hobby.

Canadian photographer Peter Mather’s long term project, Caribou People, visually explores the lives of thirteen First Nations in Canada’s remote north with the intent of uncovering a whole new perspective on ecological issues. Mather’s photo essay seeks to document the lives of a people that have always thrived on a symbiotic relationship with the roughly 200,000 porcupine caribou herd that roams their land – a herd that is directly at stake from the oil reserves beneath their hooves. But for Mather, who is based in Whitehorse, Yukon, this series speaks volumes not only about the responsibility of wealthy nations to address such concerns, but also about the need for conservation efforts in the developed world to embrace a more cultured approach. “You feel that if there is going to be a balance struck, it is going to happen in those countries that have the money and can afford not to have development. They can choose to value things other than money, and oil, and gas, and say, ‘This culture and these caribou – which are disappearing throughout the world – are more important’,” says Mather. “In Canada and the US, we have the financial ability to make those choices, whereas in some third world countries where people are just scraping by to get food on their plate, those choices would be much, much harder.”

Future preservation

In several ways, it would seem that the term “conservation photography” will soon be forgotten. This branch of photojournalism that found its roots in the documentation of wild places now bears the ominous thorns of a collective communiqué fraught with uncertainty for the future of our species and we perhaps turn instead to the need for preservation photography. As matters of climate change and habitat destruction become issues not just for the exotic animals of this planet but for the lives of billions of people, we see the images addressing such matters move from the depths of National Geographic to page one of The New York Times, and as Patrick Brown so soberly concedes: “This is no disrespect to all the war photographers that are my deep friends and colleagues, but that is nothing compared to what happens if the environment goes pear-shaped.”